Capite velato

Home | Latíné | Deutsch | Español | Français | Italiano | Magyar | Português | Română | Русский | English

⚜⚜⚜ Site Index - Key Pages ⚜⚜⚜

Contents |

Definition

In Latin, there's a phrase capite velato meaning literally “with covered head.” The term is used in Roman religious contexts to refer to the act of covering the head with a veil when performing sacrifices. It's said that the Etruscans by contrast did things 'Greek-style' (ie. capite aperto or “with bare head”).

Practice

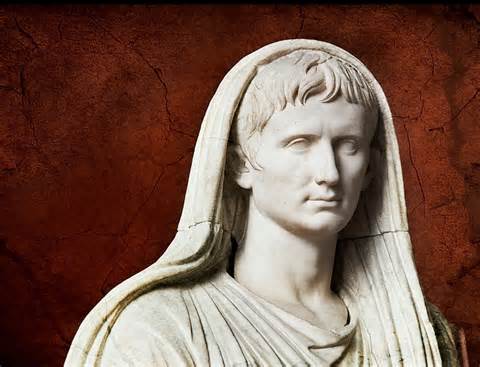

At the traditional public rituals of ancient Rome, officiants prayed, sacrificed, offered libations, and practiced augury capite velato,[1] "with the head covered" by a fold of the toga drawn up from the back. This covering of the head is a distinctive feature of Roman rite in contrast with Etruscan practice[2] or ritus graecus, "Greek rite."[3] In Roman art, the covered head is a symbol of pietas and the individual's status as a pontifex, augur or other priest.[4]

Practice prohibited by Early Christians

It has been argued that the Roman expression of piety capite velato influenced Paul's prohibition against Christians praying with covered heads: "Any man who prays or prophesies with his head covered dishonors his head."[5]

Practice in historical literature

Quoting Virgil from the Aeneid,[6] he says:

"When, in Epirus, the Trojan soothsayer prophesies to Aeneas, that his final landing point would be on the beaches of Latium[7] , he instructs him, on arrival, to turn his (veiled) head during the ceremony of thanks to the Gods, so that his gaze does not cross "some face of foe", thus desecrating the ritual."[8]

Perseus website Latin text:

- Quin, ubi transmissae steterint trans aequora classes, et positis aris iam vota in litore solves, purpureo velare comas adopertus amictu, ne qua inter sanctos ignis in honore deorum hostilis facies occurrat et omina turbet.

1910 English translation:

- Yea, even when thy fleet has crossed the main, and from new altars built along the shore thy vows to Heaven are paid, throw o'er thy head a purple mantle, veiling well thy brows, lest, while the sacrificial fire ascends in offering to the gods, thine eye behold some face of foe, and every omen fail.

Notes

- ↑ Robert E.A. Palmer, "The Deconstruction of Mommsen on Festus 462/464, or the Hazards of Interpretation", in Imperium sine fine: T. Robert S. Broughton and the Roman Republic (Franz Steiner, 1996), p. 83.

- ↑ Capite aperto, "bareheaded"; Martin Söderlind, Late Etruscan Votive Heads from Tessennano («L'Erma» di Bretschneider, 2002), p. 370

- ↑ Robert Schilling, "Roman Sacrifice", Roman and European Mythologies (University of Chicago Press, 1992), p. 78.

- ↑ Classical Sculpture: Catalogue of the Cypriot, Greek, and Roman Stone Sculpture in the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology (University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, 2006), p. 169.

- ↑ 1 Corinthians 11:4; see Neil Elliott, Liberating Paul: The Justice of God and the Politics of the Apostle (Fortress Press, 1994, 2006), p. 210 online; Bruce W. Winter, After Paul Left Corinth: The Influence of Secular Ethics and Social Change (Wm. B. Eerdmans, 2001), pp. 121–123 online, citing as the standard source D.W.J. Gill, "The Importance of Roman Portraiture for Head-Coverings in 1 Corinthians 11:2–16", Tyndale Bulletin 41 (1990) 245–260; Elaine Fantham, "Covering the Head at Rome" Ritual and Gender," in Roman Dress and the Fabrics of Culture (University of Toronto Press, 2008), p. 159, citing Richard Oster. The passage has been explained with reference to Jewish and other practices as well.

- ↑ Valerio Massimo Manfredi, "Mare greco", page 154

- ↑ Near the World War II Anzio landing beachheads.

- ↑ Virgil, Aeneid: III, 403-407