Ara

Home| Latíné | Deutsch | Español | Français | Italiano | Magyar | Português | Română | Русский | English

ARA (sg) (pl: arae)

Contents |

Definition

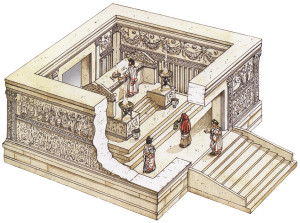

An ara is an altar, the structure on which a sacrifice is made. Arae were often open-air structures, immediately accessible to the public, whether within Rome or out elsewhere.[1]

The focal point of sacrifice was the altar. Most altars throughout the city of Rome and in the countryside would have been simple, open-air structures; they may have been located within a sacred precinct (templum), but often without an aedes (EN: temple) housing a cult image. An altar that received food offerings might also be called a mensa or "table."[2]

Perhaps the best-known Roman altar is the elaborate and Greek-influenced Ara Pacis, which has been referred to as the most representative work of Augustan art.[3]

Other major public altars included the Ara Maxima.

History

In the earliest stages of Roman life of which we now have any definite knowledge the idea of sacrifice formed an essential part of the religious conceptions of the society. This found formal expression in the word sacrificium, the making sacred of any object as the exclusive property of the divinity. In the words of Warde Fowler:

- "The word sacrificium, ... in its widest sense, may cover any religious act in which something is made sacrum, i.e. (in its legal sense), the property of a deity. ... Sacrificium is limited in practical use by the Romans themselves to offerings, animal or cereal, made on the spot where the deity had taken up his residence, or at some place on the boundary of land or city (e. g., the city gate) which was under his protection, or (in later times at least) at a temporary altar erected during a campaign."

The destruction of the offering in a manner prescribed by ritual, typifying and securing its complete transference to the deity, was the essential element of sacrifice.

Many theories have been advanced to account for the origin of sacrifice, but it is difficult to find in any one of them an explanation that is completely satisfactory for all cases. One of the weaknesses of most of these theories is that they have been framed with the idea of universal application, but as has been pointed out in recent years, it is hardly probable that all forms of sacrifice arose from the same primitive conception. The fundamental idea, however, seems to be that the gods are capable of sending good or ill; if man is to be happy, the favor of these powers must be won and their ill-will averted. The chief means to this end is the sacrifice, whether it be expiatory, honorific or sacramental in origin.

In the simple life of early Rome the sacrifices must have been performed in a manner fitting the character and environment of the people. For these sacrifices some primitive form of altar would be required. A few unhewn stones 6 or a temporary structure of turf and branches would be sufficient for the simple ceremonial of this early worship. Gradually these temporary altars would give place to more permanent structures, where the sacrifices were offered in a manner but little more elaborate than earlier generations had known.

By degrees, with the growth of the Roman state, this simple worship became more complex and the official cults and priesthoods were established. Doubtless much was lost in this process of evolution and through the growing intercourse with Etruria and Greece much was gained, but through all these changes the idea of sacrifice remained as a central and essential feature of Roman religion, both domestic and national, and of necessity the altar held a most important place in all religious observances of which the rite of sacrifice formed a part.[4]

In descriptions of Roman sacrificial rites five different terms for designating the altars are commonly used:

- focus

- foculus

- mensa

- ara, and

- altaria

Of these, the last two appear most frequently, but the others are used often enough to make an investigation of their meaning necessary.

The ancient etymologists derive the word focus from fovere, and Servius adds in one passage that a focus is an indispensable adjunct of both public and private sacrifices. However unsound etymologically this derivation may be, it undoubtedly expresses the real significance of the focus, that it was a place where the sacred fire was tended, at first the hearth of the individual home, the center of the domestic worship, but with the gradual growth of the state religion becoming a necessary adjunct of the public sacrificial altar. The use of the word in the familiar phrase arae focique as expressive of all that was most sacred from a religious point of view was an attempt to unite in one the public and private aspects of religion.[5]

Originally the term focus may have been applied to the part of the altar which actually contained the sacrificial fire, or to a small portable brazier placed upon the altar at the time of sacrifice, but in most cases where it is used in, descriptions of sacrificial rites it seems to be practically synonymous with ara or altaria. Garlands are hung upon it; it may be constructed of turf; the exta of the victims are burned upon it. All this shows that its original significance was gradually lost and that the distinction between it and altaria and ara came to be disregarded, especially by the poets.[6]

The term foculus may be dismissed in a few words. It appears frequently in the Acta Fratrum Arvalium and seems there to refer to a portable vessel or tripod, which in certain instances at least was of silver. It could not have been large, as it was carried about from place to place.[7]

The mensa or table was a necessary part of the furniture of the sanctuary. Here were kept the sacred vessels and implements when they were not in actual use, and here the offerings of the worshippers were deposited. Festus gives the term anclabris as a special name for the sacred table. As a sacrificial term, mensa seems to have preserved more of its original meaning than did focus, although there is mention of a sacrifice made upon a mensa, which in this case, therefore, can hardly denote an ordinary table for the sanctuary. Cicero uses the term in regard to a monument for the dead, presumably the ordinary grave-altar. A second passage of Festus shows that mensae were used as altars in aedibus sacris. This qualifying phrase is probably to be explained by the fact that the actual sacrificial altars were usually, for reasons of convenience, placed outside the temple proper. A passage in Petronius gives a widely different meaning to the term. Here it appears to be an immediate adjunct of the altar itself, a sort of brazier or grate placed upon it at the time of sacrifice.[8]

In discussing ara and altaria, the terms most frequently used, it may be well to take up the derivation first. Festus gives as one explanation of the derivation of altaria the following:

- "altaria ab altitudine dicta sunt, quod antiqui diis superis in aedificiis a terra exaltatis sacrafaciebant." [9]

This may be correct, though other explanations have been suggested by modern scholars.

The word ara appears to be the more ancient. There is abundant testimony to the primitive form asa, before the law of rhotacism became effective. This old form is closely connected with the Umbrian and Marsian asa and aso, Oscan aasa, and Volecian asif, which have a common root as meaning to burn or glow. The root meaning of the word would thus seem to be a place for burnt offerings, although in the earliest times now known to us, it had become the common designation for any place of offering, without regard to the use of fire in the ritual. The ancient writers seem to be confused and uncertain as to the derivation of the word. Modern scholars are fairly well agreed in finding in the root the idea of burning.[10]

The Romans seems to have been aware of an original distinction between ara and altaria, although in practice this distinction was commonly disregarded. Servius has two important passages bearing on this point:

- "superorum et arae sunt et altaria, inferorum tantum arae. Novimus enim aras et diis esse superis et inferis consecratas, altaria vero esse superorum tantum deorum."[11]

Varro, quoted by Servius in the first of these passages, makes the further distinction that"

- "diis superis altaria, terrestribus aras, inferis focos dicari." [12]

In a third passage Servius makes this distinction:

- "mortuorum arae, deorum altaria dicuntur, . . . quamvis hoc frequenter poeta ipse confundat" [13]

and Isidorus supports this when he says:

- "inter altaria et aras hoc interest, quod altaria deo ponuntur, arae etiam defunttis." [14]

That arae as opposed to altaria were originally connected with the cult of the heroized dead is shown by this same commentary of Servius on Eclogue. V, 66, where it is expressly stated that altaria were erected to Apollo, quasi deo, while Daphnis by virtue of his mortal nature received only arae. Too much importance, however, must not be attached to passages of this sort, since we have the testimony of Servius that Vergil was not consistent in his use of the terms, and other writers were probably no more exact than he. The choice of one word rather than the other was doubtless often determined merely by metrical or rhetorical considerations. Altaria, as the more sonorous term, is frequently preferred by the poets. A large number of cases might be cited where apparently there is a distinction between ara and altaria, but these would be counterbalanced by an equally large number of cases where the terms are used promiscuously. An examination of the literary evidence fails to support the statements of Servius and Isidorus quoted above, that both arae and alia/no, were used in the worship of the celestial divinities, while sacrifice was offered to the gods of the lower world on arae, alone. One illustration may suffice: in I, 46 of the Punica Silius uses altaria as synonymous with an arae previously used, which he expressly says were erected caelique diis Ereboque potenti.[15]

From a comparison of passages where the two terms are used, with the support of etymology, certain writers have tried to show that altaria was the term used for the upper part of the altar, as contrasted with ara, the base of the structure. Others again have attempted to limit altaria to a separate portable support or frame of metal or terra cotta placed upon the ara at the time of sacrifice. That such accessories were used is abundantly attested by the monuments, and they would be a necessity in the case of marble altars which would be calcined by direct contact with fire. In spite, however, of the evidence for this practice, the use of the term altaria as applied only to these accessories is scarcely justified by the literary evidence.[16]

Types of Roman Altars

Roman altars can be divided into two main classes:[17]

- Those with a curving profile or outline, and

- Those with a straight profile.

The first class, though numerically much the smaller, far surpasses the second in interest and importance.

The second class has been divided into four groups:

- (A) altars having pulvini or bolsters at the sides;

- (B) those with pointed appendages or "horns" at the corners of the top;

- (C) flat-topped altars;

- (D) altars with shallow depressions of various shapes and depths in the upper surface.

In a few instances an altar may be classified in two of these groups for example, an altar with pulvini or horns may also have the depression characteristic of Class II, D but as a general rule the divisions are clearly marked. The absence in most cases of any satisfactory criteria for dating has made even a roughly chronological arrangement impossible. The altars have therefore been grouped within the different classes according to their present location.[18]

Overview of Roman Altar Construction

- Roman sacrificial altars present in general two widely differing types, those with curving profiles and those with straight profiles.[19]

- The first of these types was derived from Etruria and bears a marked resemblance to altar-forms employed by peoples further to the East, especially the Babylonians and the bearers of the Aegean civilization.[20]

- The second of the two types was too widely diffused and too little individualized to afford any conclusions as to the relations of the peoples using it.[21]

- The decoration of the altars was largely determined by their function as the chief accessory of the sacrifice and reflects the more important art of the time.[22]

- Although the sacrificial altars form a group of comparatively unimportant monuments, they may yet serve to play some small part in determining the historical and artistic relations of the forces that produced them.[23]

List of Roman Altars

This is a list of ancient Roman altars, that is, altars known to have been located within the city of ancient Rome, or altars established in territories under Roman rule before Christianity became the official religion of the Roman Empire.[24]

City of Rome

- Ara Pacis, the Altar of Peace

- Ara Maxima, the Great Altar of Hercules

- Ara Calvini, a restoration of an archaic altar dedicated to sei deo sei divae, "whichever god or goddess"

- Ara Martis. There was more than one Altar of Mars: In the Campus Martius, near the Villa Publica: The establishment of this altar was attributed to Numa Pompilius, the semi-legendary second king of Rome. It was located in the center of the Campus, to the east of the Palus Caprae. "The Altar of Mars and the Villa Publica defined the area where the most important electoral functions of the Republic took place." The comitia centuriata and the comitia tributa met in the Campus. "Generals preparing to celebrate a triumph offered the sacrifice of the secunda spolia at the Ara Martis while they waited for the necessary senatorial approval to enter the city."[25]

- Ara Saepta, otherwise known as the Altar of Aius Locutius

- Altar of Consus

- Altar of the Julian gens, see R. under GENS IULIA, ara[26]

- Altar of the Divine Matidia, the mother-in-law of Hadrian made diva[27]

- Altar of Fortuna Redux[28]

- Amicitiae Ara, decreed by the senate but location (or whether it was even built) unknown

- Altar of Dis Pater and Prosperpina

- Altar of Domitius Ahenobarbus

- Ara Marmorea, "marble altar" known from two inscriptions found near the Porta Capena[30]

- Arae Incendii Neronis, ought to have a section in Great Fire article; see R p. 21

- Ara Pietatis Augustae

- Ara Saturni

- Altar for the Lares Augusti and Genii Caesarum of a vicus, given by four magistri vici primi.[31]

- Altar for the Lares Augusti, given to the Vicus Aeculeti by its magistri vici.[32]

- Altar to Aesculapius Augustus, dedicated by a minister vicus of Tiberina.[33]

- Altar to Concordia Augusta.[34]

- Ara Providentia Augusta, attested by the Arval Acts and later coin inscriptions; location unknown.[35]

- Altar to Bona Dea, dedicated by Anteros.[36]

- Altar to Cautes and Cautopates, divine attendants of Mithras, symbolizing respectively dawn and sunset. Inscription: "Deo Cautae Aur. Sabinus Pater huius loci Tiberius Quintianus ex voto posuerunt." ("To the god Cautes. Aurelius Sabinus, Pater of this place [and] Tiberius Quintianus, set this up in fulfilment of a vow.") Dedicated by Aurelius Sabinus, pater of the mithraeum of the castra peregrina of the Imperial horseguards (equites singulares). Marble, reign of Commodus (180-192 CE). From the area of S. Stefano Rotondo, Rome. [from the description at Commons)

Hispania

- Altar de Lucius Iunius Paetus, from the Roman theater of Cartagena (Museo del Teatro Romano de Cartagena. AE 1992, 01077)

Africa

- Altar of Marazgu Augustus, Libya. A Berber deity identified with Augustus, in a local form of Imperial cult

- Altars (several) to Dii Magifie Augusti, local expressions of Imperial cult

- Altars to Roma with the divus Augustus, at Leptis Magna and Mactar.

Gaul

- Altar of Dea Roma at the Sanctuary of the Three Gauls in Lugdunum (Lyon)

- Ara Numinis Augusti ("Altar of the Numen of Augustus") at Narbonne.[37]

Britannia

- Altar to Fortuna, military dedication at Blatobulgium (Birrens), an Antonine Wall fort.[38]

- Altar to the Genius of Britannia (Genio Terrae Britannicae), a centurion's dedication at Auchendavy fort, Antonine Wall.[39]

Germania Inferior

- Altar of Vagdavercustis, at Colonia Claudia Ara Agrippinensium (Cologne). Dedicated in the late 2nd century AD by Titus Flavius Constans, a Praetorian prefect at Roman Cologne, Germania Inferior. He is shown with his assistants, performing a sacrifice

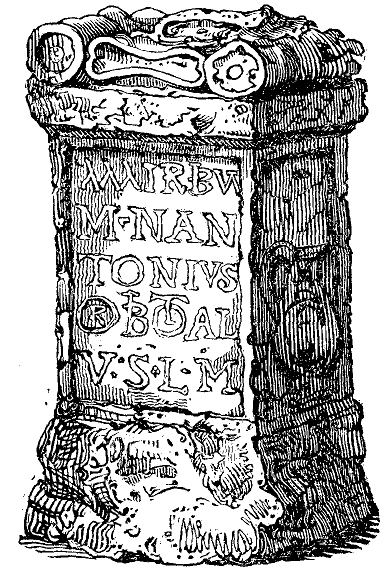

- Votive altar for the goddess Hustrge: (to the) Goddess Hustrge and on her order has Valerius Silvester, decurio (council) of the Municipium Batavorum erected this altar, freely and deservedly.. DEAE HURSTRGE Ex P(raecepto) EIUS VAL(erius) SILVESTE[r] DEC(urio) M(unicipii) BAT(avorum) POS(uit) L(ibens) M(erito) (Bogaers, BROB, p. 287-290 (AE 1958, 38= 1959, 10). Found in the vinicity of Tiel, the Netherlands, Museum Het Valkhof, Nijmegen, The Netherlands.[40]

Notes

- ↑ Mary Beard, J.A. North, and S.R.F. Price, Religions of Rome: A Sourcebook (Cambridge University Press, 1998), p. 83.

- ↑ Ulrike Egelhaaf-Gaiser, "Roman Cult Sites: A Pragmatic Approach," in A Companion to Roman Religion (Blackwell, 2007), p. 206.

- ↑ Karl Galinsky, Augustan Culture: An Interpretive Introduction (Princeton University Press, 1996), p. 141.

- ↑ Helen Cox Bowerman, Roman Sacrificial Altars: An Archaeological Study of Monuments in Rome http://www.archive.org/stream/romansacrificial00boweuoft/romansacrificial00boweuoft_djvu.txt

- ↑ Helen Cox Bowerman, Roman Sacrificial Altars: An Archaeological Study of Monuments in Rome http://www.archive.org/stream/romansacrificial00boweuoft/romansacrificial00boweuoft_djvu.txt

- ↑ Helen Cox Bowerman, Roman Sacrificial Altars: An Archaeological Study of Monuments in Rome http://www.archive.org/stream/romansacrificial00boweuoft/romansacrificial00boweuoft_djvu.txt

- ↑ Helen Cox Bowerman, Roman Sacrificial Altars: An Archaeological Study of Monuments in Rome http://www.archive.org/stream/romansacrificial00boweuoft/romansacrificial00boweuoft_djvu.txt

- ↑ Helen Cox Bowerman, Roman Sacrificial Altars: An Archaeological Study of Monuments in Rome http://www.archive.org/stream/romansacrificial00boweuoft/romansacrificial00boweuoft_djvu.txt

- ↑ Helen Cox Bowerman, Roman Sacrificial Altars: An Archaeological Study of Monuments in Rome http://www.archive.org/stream/romansacrificial00boweuoft/romansacrificial00boweuoft_djvu.txt

- ↑ Helen Cox Bowerman, Roman Sacrificial Altars: An Archaeological Study of Monuments in Rome http://www.archive.org/stream/romansacrificial00boweuoft/romansacrificial00boweuoft_djvu.txt

- ↑ Helen Cox Bowerman, Roman Sacrificial Altars: An Archaeological Study of Monuments in Rome http://www.archive.org/stream/romansacrificial00boweuoft/romansacrificial00boweuoft_djvu.txt

- ↑ Helen Cox Bowerman, Roman Sacrificial Altars: An Archaeological Study of Monuments in Rome http://www.archive.org/stream/romansacrificial00boweuoft/romansacrificial00boweuoft_djvu.txt

- ↑ Helen Cox Bowerman, Roman Sacrificial Altars: An Archaeological Study of Monuments in Rome http://www.archive.org/stream/romansacrificial00boweuoft/romansacrificial00boweuoft_djvu.txt

- ↑ Helen Cox Bowerman, Roman Sacrificial Altars: An Archaeological Study of Monuments in Rome http://www.archive.org/stream/romansacrificial00boweuoft/romansacrificial00boweuoft_djvu.txt

- ↑ Helen Cox Bowerman, Roman Sacrificial Altars: An Archaeological Study of Monuments in Rome http://www.archive.org/stream/romansacrificial00boweuoft/romansacrificial00boweuoft_djvu.txt

- ↑ Helen Cox Bowerman, Roman Sacrificial Altars: An Archaeological Study of Monuments in Rome http://www.archive.org/stream/romansacrificial00boweuoft/romansacrificial00boweuoft_djvu.txt

- ↑ Helen Cox Bowerman, Roman Sacrificial Altars: An Archaeological Study of Monuments in Rome http://www.archive.org/stream/romansacrificial00boweuoft/romansacrificial00boweuoft_djvu.txt

- ↑ Helen Cox Bowerman, Roman Sacrificial Altars: An Archaeological Study of Monuments in Rome http://www.archive.org/stream/romansacrificial00boweuoft/romansacrificial00boweuoft_djvu.txt

- ↑ Helen Cox Bowerman, Roman Sacrificial Altars: An Archaeological Study of Monuments in Rome http://www.archive.org/stream/romansacrificial00boweuoft/romansacrificial00boweuoft_djvu.txt

- ↑ Helen Cox Bowerman, Roman Sacrificial Altars: An Archaeological Study of Monuments in Rome http://www.archive.org/stream/romansacrificial00boweuoft/romansacrificial00boweuoft_djvu.txt

- ↑ Helen Cox Bowerman, Roman Sacrificial Altars: An Archaeological Study of Monuments in Rome http://www.archive.org/stream/romansacrificial00boweuoft/romansacrificial00boweuoft_djvu.txt

- ↑ Helen Cox Bowerman, Roman Sacrificial Altars: An Archaeological Study of Monuments in Rome http://www.archive.org/stream/romansacrificial00boweuoft/romansacrificial00boweuoft_djvu.txt

- ↑ Helen Cox Bowerman, Roman Sacrificial Altars: An Archaeological Study of Monuments in Rome http://www.archive.org/stream/romansacrificial00boweuoft/romansacrificial00boweuoft_djvu.txt

- ↑ Helen Cox Bowerman, Roman Sacrificial Altars: An Archaeological Study of Monuments in Rome http://www.archive.org/stream/romansacrificial00boweuoft/romansacrificial00boweuoft_djvu.txt

- ↑ Paul Rehak and John G. Younger, Imperium and Cosmos: Augustus and the Northern Campus Martius (University of Wisconsin Press, 2006), pp. 11–12 online.

- ↑ Lott, pp.199 - 200, and Fig. 13.

- ↑ Lott, pp.199 - 200, and Fig. 13.

- ↑ Lott, p.212.

- ↑ Richardson, p.322.

- ↑ CIL 6.9403 = ILS 7713, CIL 6.10020 and IGUR 1342; R p. 21.

- ↑ John Lott, The neighborhoods of Augustan Rome, pp.184 - 185, and Fig. 12.

- ↑ Lott, pp.199 - 200, and Fig. 13.

- ↑ Lott, pp.199 - 200, and Fig. 13.

- ↑ Lott, p.212.

- ↑ Richardson, p.322.

- ↑ CIL VI 55, from Regio II, Imperial era; Hendrik H. J. Brouwer, Bona Dea: the sources and a description of the cult, Études préliminaires aux religions orientales dans l'Empire romain, 110, BRILL, 1989, p.27.

- ↑ CIL 12.4333 = ILS 112, as cited by Duncan Fishwick, Imperial Cult in the Latin West (Brill, 1990), vol. II.1, p. 610.

- ↑ Roman-Britain.org

- ↑ Huntsearch.gla.ac.uk

- ↑ CIL VI 55, from Regio II, Imperial era; Hendrik H. J. Brouwer, Bona Dea: the sources and a description of the cult, Études préliminaires aux religions orientales dans l'Empire romain, 110, BRILL, 1989, p.27.

Additional References

- 1. [Helen Cox Bowerman, Roman Sacrificial Altars: An Archaeological Study of Monuments in Rome http://www.archive.org/stream/romansacrificial00boweuoft/romansacrificial00boweuoft_djvu.txt ]

- 2. Mary Beard, J.A. North, and S.R.F. Price, Religions of Rome: A Sourcebook (Cambridge University Press, 1998), p. 83.

- 3. Ulrike Egelhaaf-Gaiser, "Roman Cult Sites: A Pragmatic Approach," in A Companion to Roman Religion (Blackwell, 2007), p. 206.

- 4. Karl Galinsky, Augustan Culture: An Interpretive Introduction (Princeton University Press, 1996), p. 141.